Riverside Cemetery Civil War Monument

Your donation can help restore Norwalk’s Civil War monument

The Norwalk Riverside Cemetery Civil War Monument is currently in pieces. The rifle and one hand are missing. The monument is currently stored in collections at the Norwalk Historical Society Museum.

Introduction

Since its installation and dedication in 1889, the Soldiers Monument located in Norwalk’s Riverside Cemetery has suffered from deterioration and vandalism. The zinc Civil War soldier once graced a seven‐foot tall granite base (still in situ) until it deteriorated to the point of collapse. Vandals further contributed to the statue’s decline, first by stealing the rifle carried by the soldier, and eventually by pulling the statue off its base in 2002.

Significance

Before the Soldiers Monument was vandalized, the most interesting aspect was its material. While the base was made of traditional granite, the statue of the Civil War soldier itself was made of zinc. Thousands of Civil War memorials were erected in the years directly following the end of the war (so much so that many states have guidebooks to highlight their individual sites), but the use of zinc was never as common as bronze or cut stone.

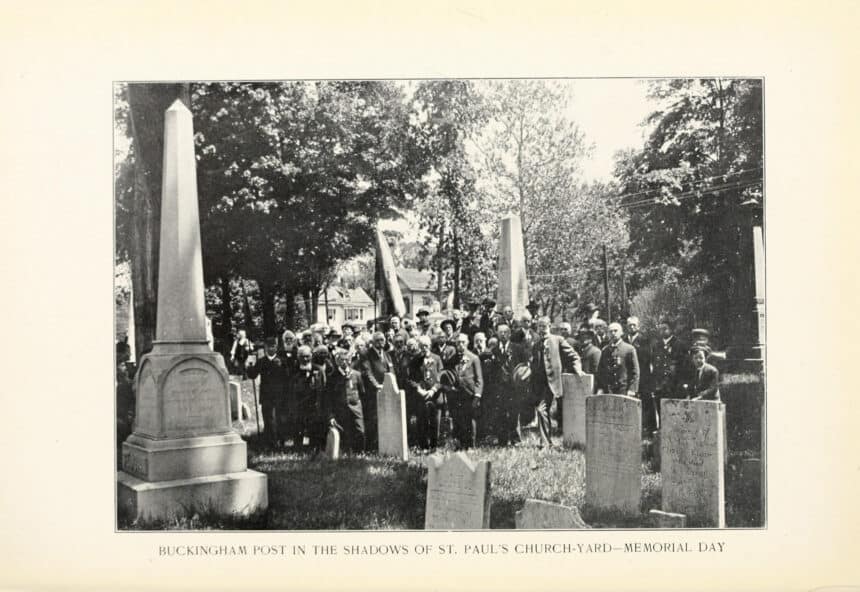

It was the wish of the Post that the monument was not to be of an elaborate or expensive character, but such as would honor the hallowed spot, and mark it for future generations as the resting place of those who fought to save the Union in its hour of peril. But the memorial we to-day dedicate is something even more than in honor of our dead comrades. In the natural course of events, those solid blocks of granite will stand for ages – even long after the statue which surmounts them – and to future generations, to whom the Grand Army of the Republic is unknown, or but a faint and distant memory, and when this cemetery shall have become a beautiful city of the dead, the inscription on yonder stone will point to the fact that in the year of our Lord 1889, there existed in the town of Norwalk, a relic of the great War of the Rebellion, known as Buckingham Post No. 12, Department of Connecticut Grand Army of the Republic. The monument is therefore a memorial of the Post.”

GIVE TO HELP THE HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Description

The soldier figure molded of zinc is a typical standing Civil War figure type, of which stone, bronze and other materials were used in countless places across the country. When in place, the figure stood in contrapposto, leaning on his proper right leg, arms draped easily on top of a rifle (now missing, though we believe we have identified the missing object and will be able to retrieve it). Wearing his dress blue overcoat with cap, the figure’s head is tilted slightly to the proper right and wears a droopy mustache. Earlier descriptions of the monument (before it was pulled down by vandals) describe the figure as leaning unnaturally backwards – a sign that the statue had begun to “creep” backwards due to the metal collapsing.

At this time it is unknown how many times the monument was painted, but areas of paint still exist as seen on the face. According to Ransom’s description, the J.W. Fiske Iron Works was a “prominent New York City foundry,” who acted as a “middleman” for zinc castings done by M.J. Seeling & Co., of Brooklyn. Further, in 2001 when Ransom completed this SOS! Survey questionnaire, eleven other Fiske zinc monuments had been located in other places in the East and mid-west.

The monument base and pedestal are grey granite, and the polished front surface in incised with the following:

In Honor of

Our Dead Comrades

Who Fought

To Save the Union

In the War of 1861‐1865

Erected By

Buckingham Post No. 12

Dept of Conn G.A.R. 1889