Augustus Washington, Daguerreotypist

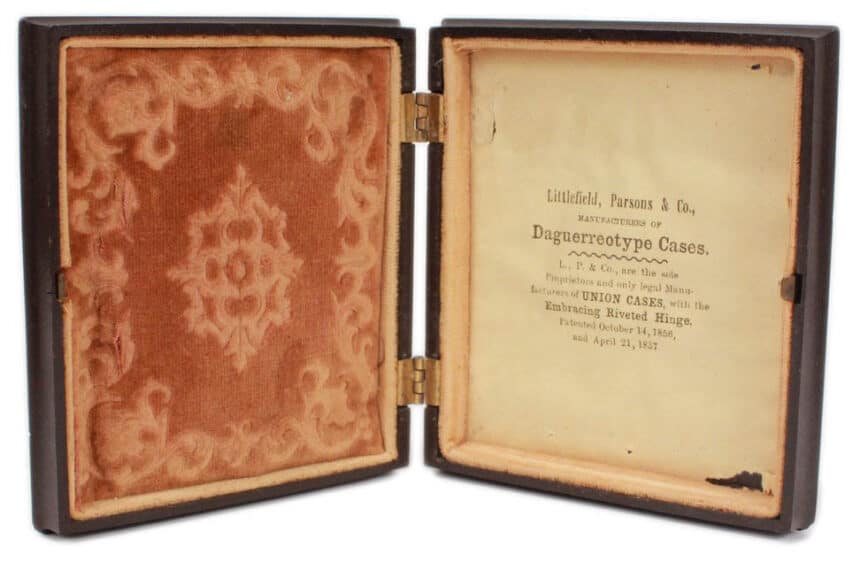

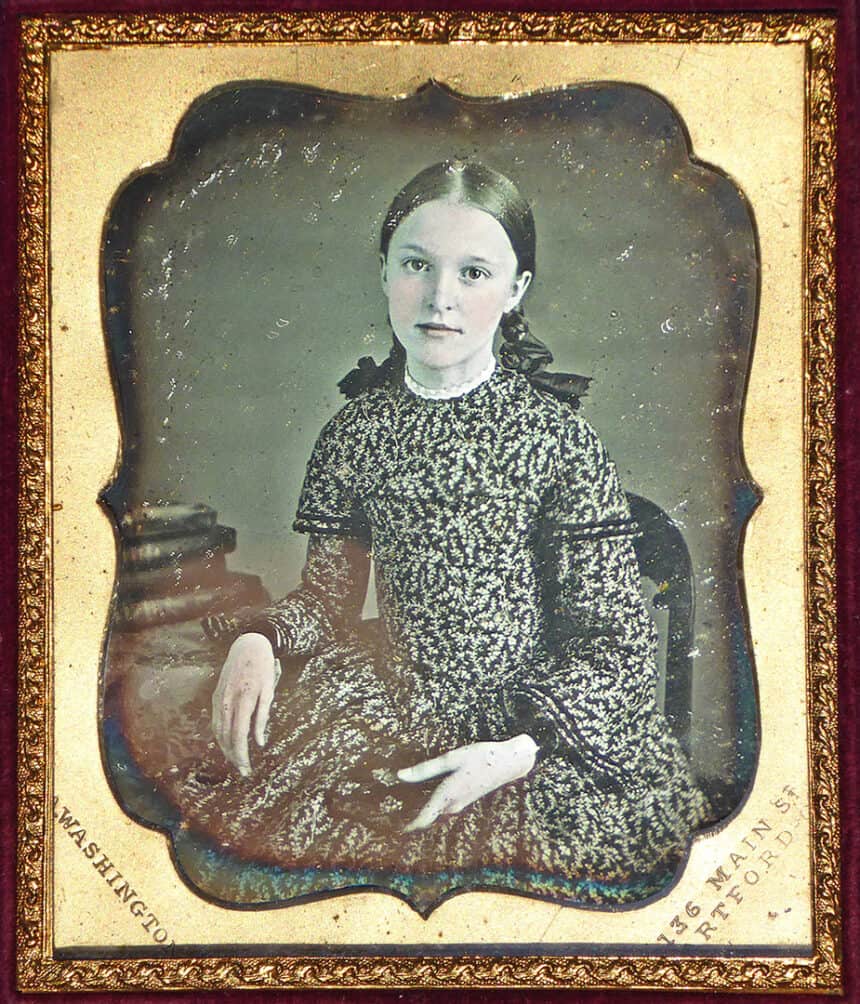

As you can see from the stamp in the corners of Mary and Charlotte Hill’s daguerreotypes, they were taken at the studio of Augustus Washington. Washington was an African-American daguerreotypist whose successful Hartford studio was open from 1846 to 1853.

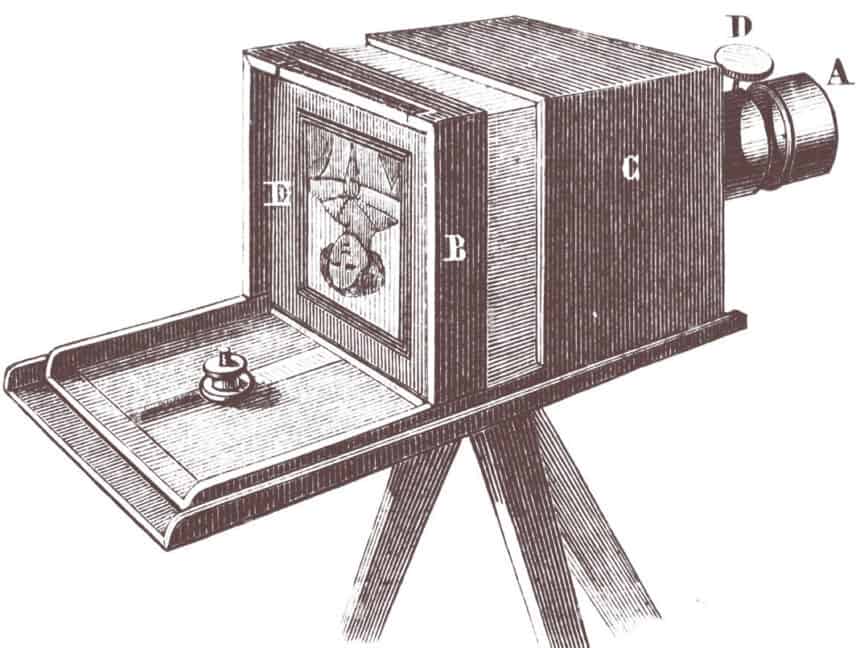

The son of a former slave, Washington learned how to make daguerreotypes to support his studies at Dartmouth. His debt proved too great, however, and he left college to direct a Hartford school for black children, Talcott Street Congregational Church’s North African School. Eventually he returned to photography full time and opened a studio there in 1846.

Despite his success, by 1853 Washington had decided to emigrate with his family to Liberia because of the barriers he found in the United States. It would be another decade before slavery was abolished, for instance, and the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act had eliminated the risks for profiteers who illegally kidnapped free Northern blacks and sold them into slavery.

In Liberia, Washington ran a daguerreotype studio from 1853 until his death in 1875.

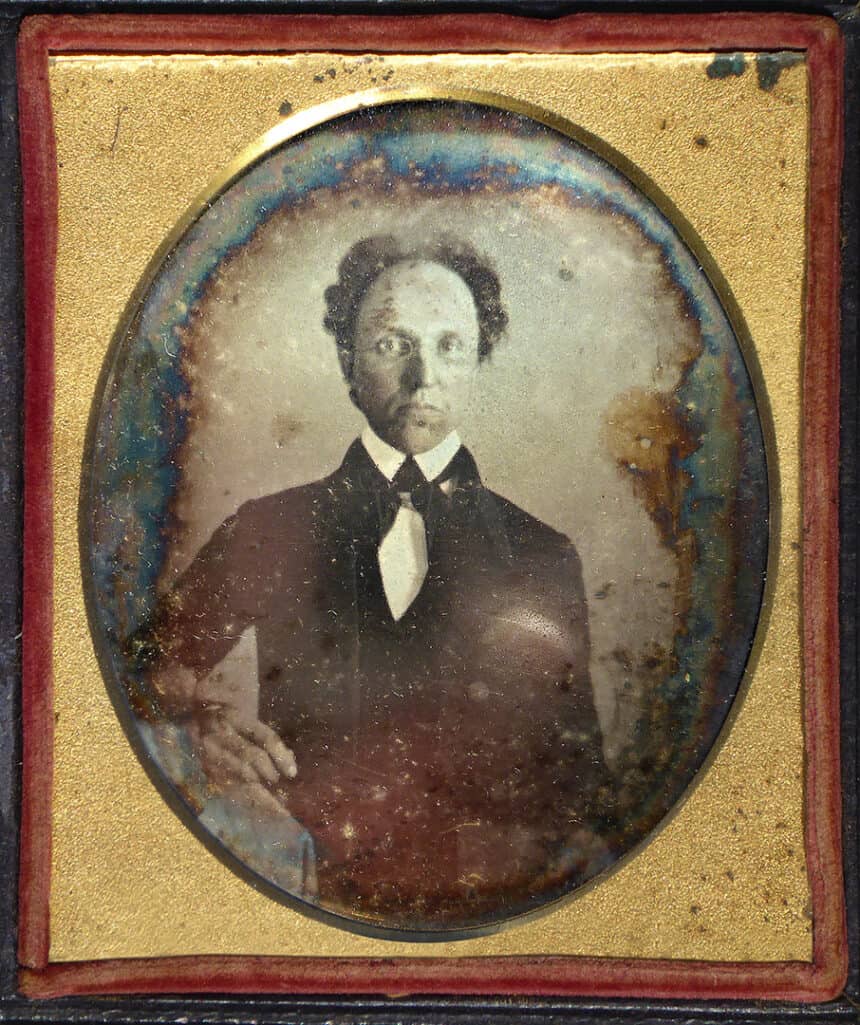

BACKGROUND:

Chancy Brown | Daguerreotype | Augustus Washington (1820/1821-1875) Liberia, Africa, 1856-60 | DAG no. 1004 Library of Congress