a collaborative series of exhibits and events celebrating the art of the quilt

Introduction

Norwalk Quilt Trail Coordinator Laura Macaluso

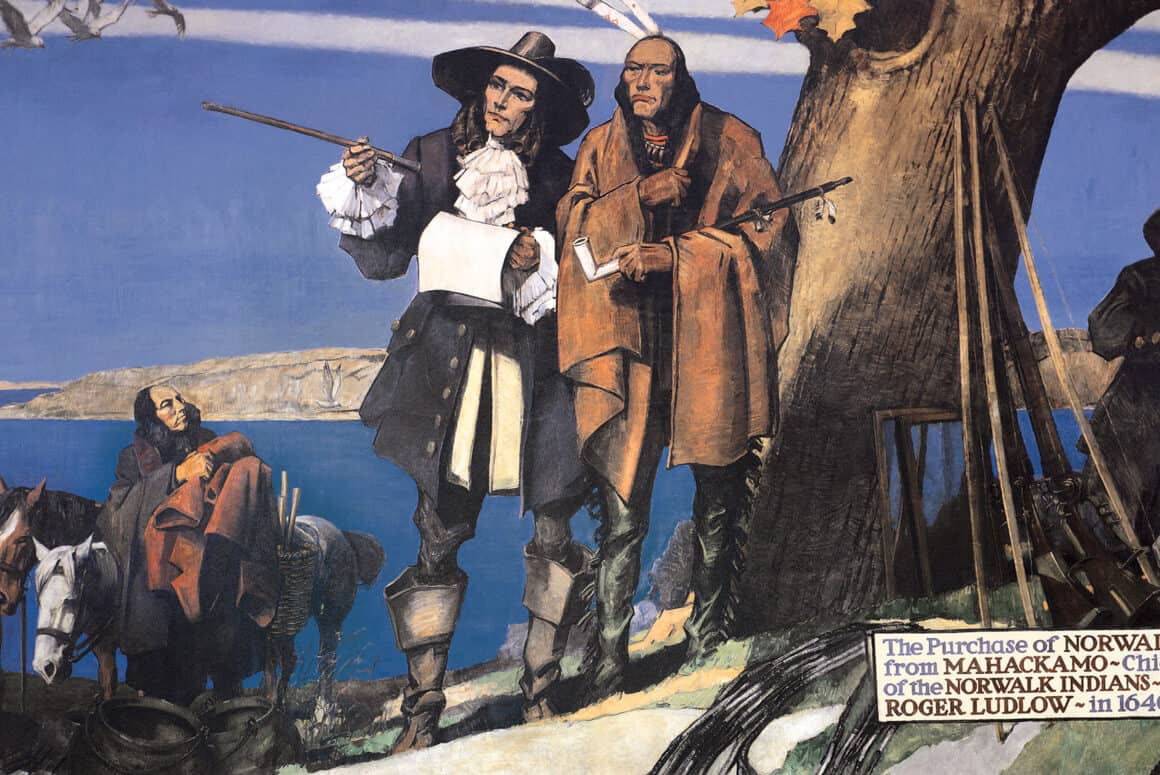

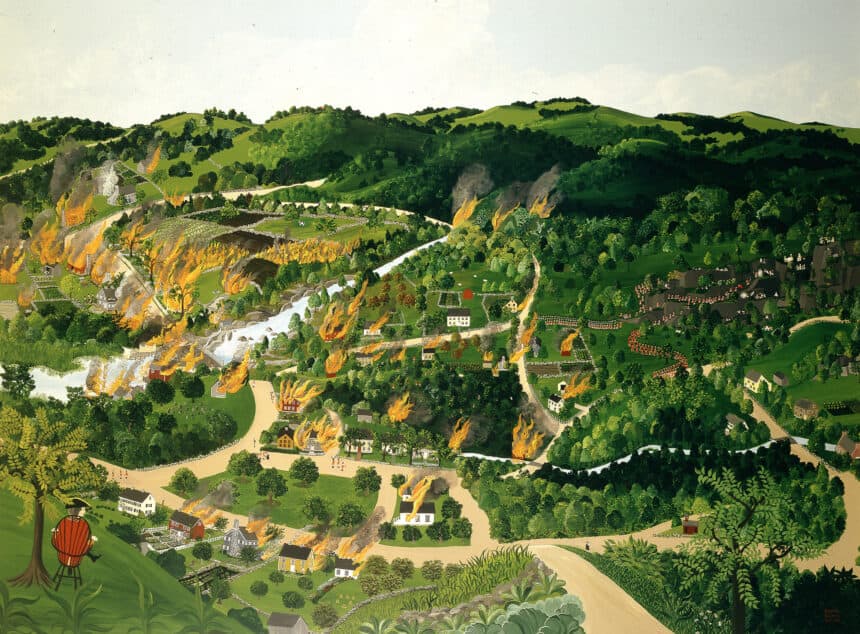

As with most contemporary Connecticut cities, Norwalk began as an agricultural endeavor, with early families sustaining themselves through farming and fishing. With large families to provide for, women were intensely engaged in the production of food and textiles. Significant portions of time were spent in processing the wool and flax necessary for spinning and weaving.

Although quilts were made during the Colonial period, this was not an occupation that engaged the average woman or household. Quilts were a luxury item, blankets were less expensive, and producing fiber was for necessities such as household textiles and clothing.

By the mid 1800’s the New York/New Haven Railroad began operating through Norwalk. As with many towns along the Connecticut coast, this development, coupled with the rise in manufacturing throughout the 19th century, created a successful industrial economic base. Iron works, clothing manufacturers, hatters, and shoe and oyster factories all had a significant presence in Norwalk.

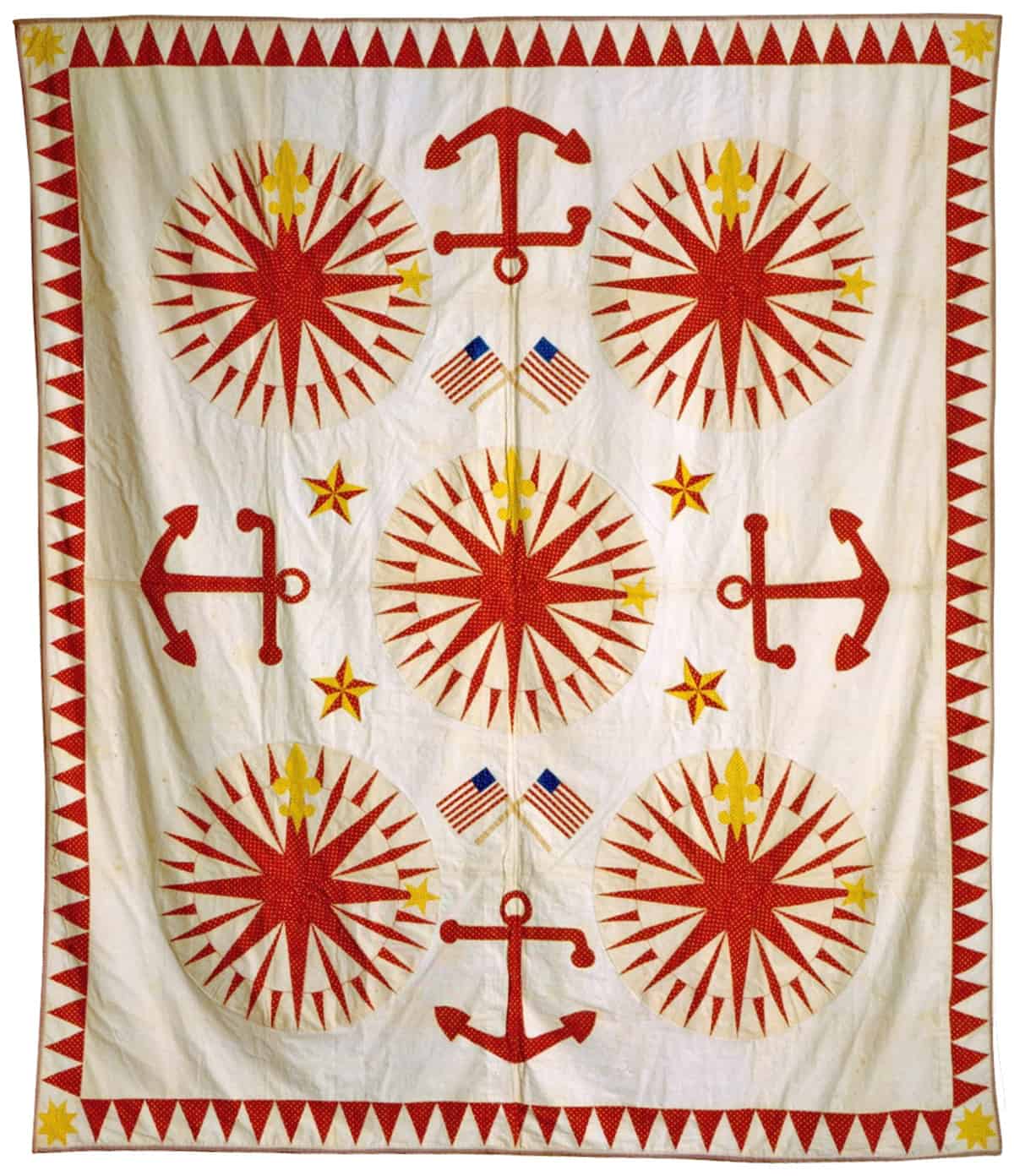

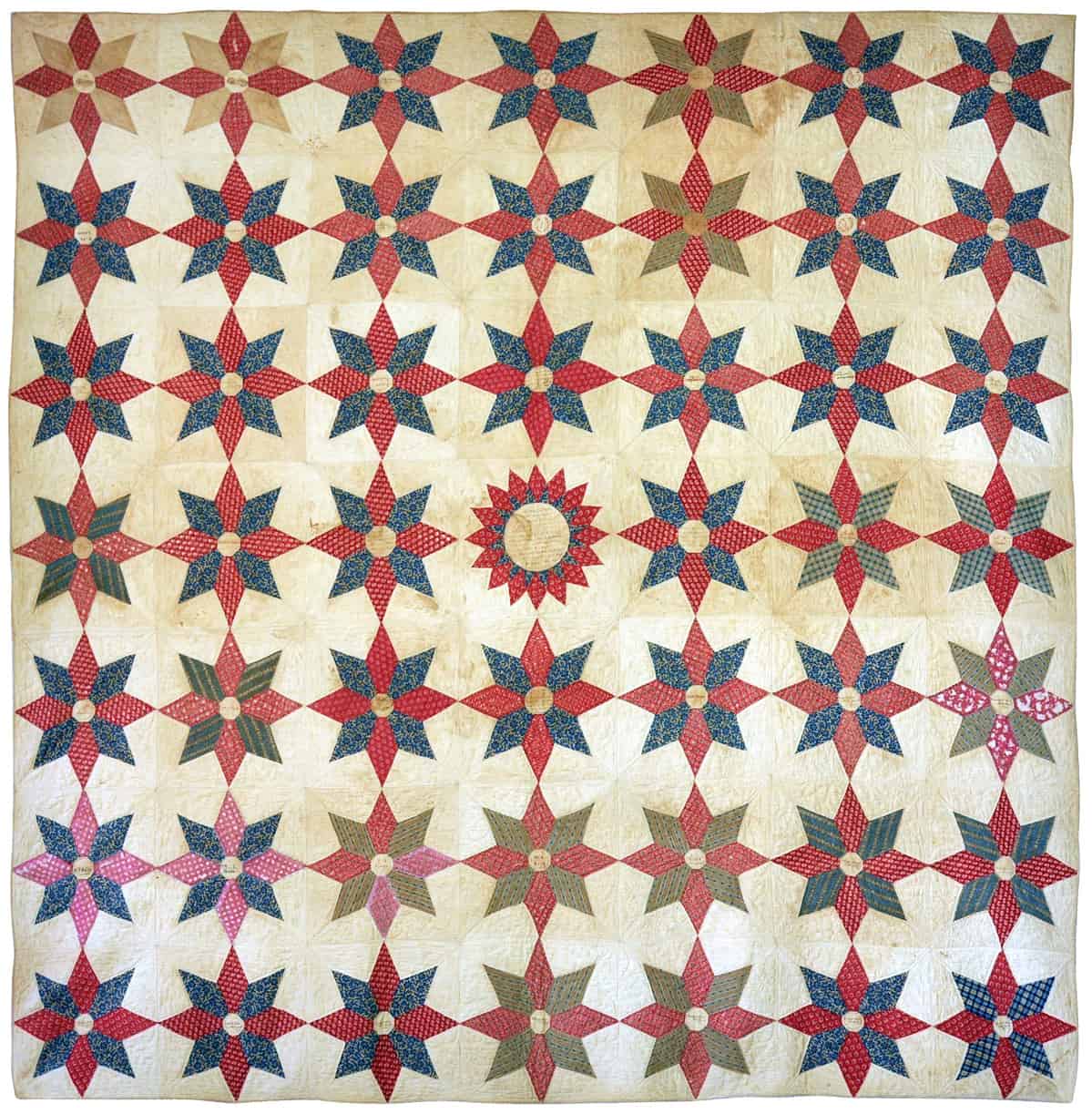

Maritime activities along the Sound and in the many ship building yards and oyster houses boomed. A superb example of Norwalk’s maritime heritage is seen in the Mariner’s Compass quilt, designed by Captain Charles Selleck and pieced by his wife Samantha in 1860, now in the collection of the Connecticut Historical Society.

From the 1840’s though the 1910’s Norwalk was the oyster capital of the world due to the riches of its estuaries, which, combined with the protection of the Norwalk Islands, provided an ideal nursery for the growing and nurturing of oysters. They were shipped all over the country and also to Europe by train and boat.

A red and white Hawaiian style quilt will illustrate the wide influence of seafaring and global trade, in which American raw materials such as cotton were part of a global cultural and economic exchange.

During this time, production of textiles moved from the home to factories. New England’s iconic mills produced much of the fabric in the United States. Although women made up the majority of the workforce, the advent of factory based work and the proliferation of new domestic devices affording them a new and welcome phenomenon: leisure time.

One unique example of quilting in Norwalk speaks to this heritage: ribbon strips from clothing and hat manufacturers were sewn together, creating lively and useful coverings – and, today, remind us of Norwalk’s industrial past.

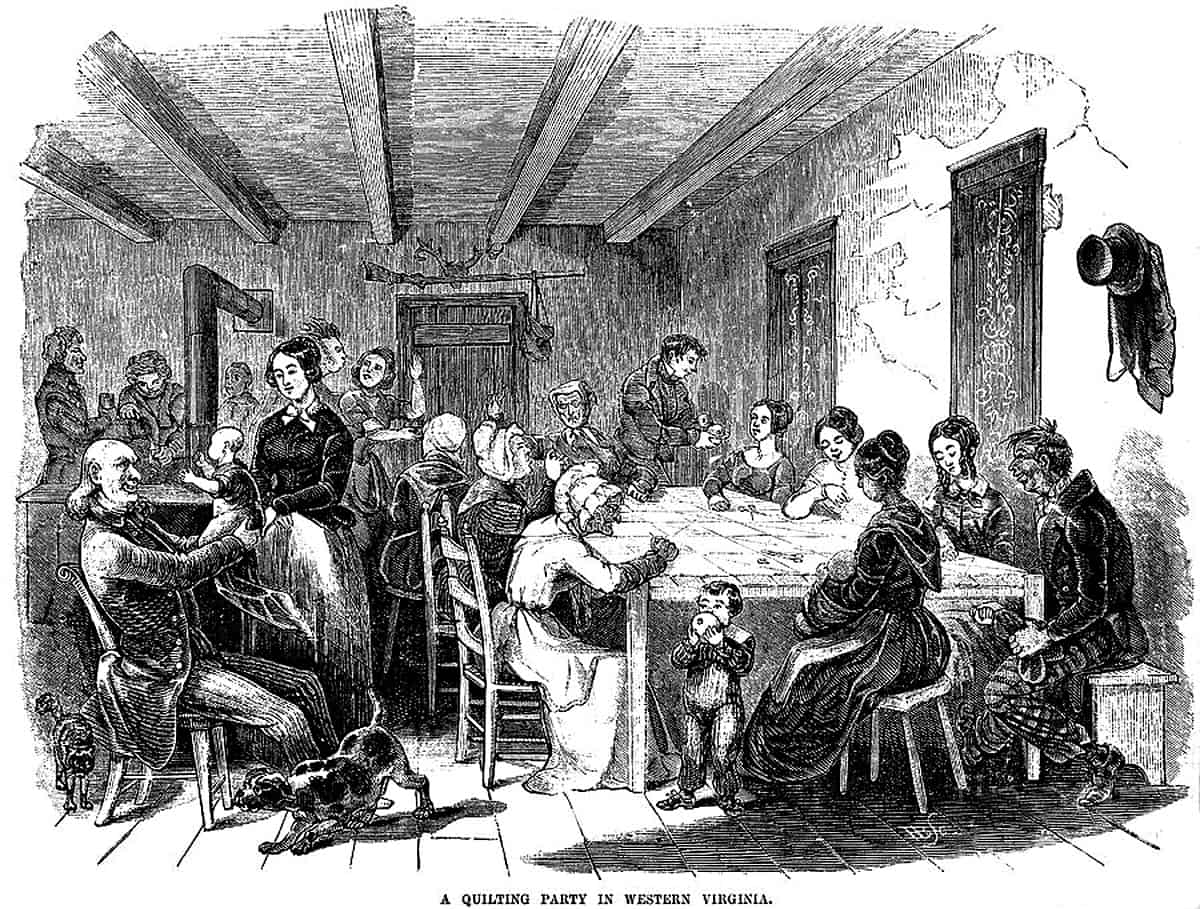

In the Victorian era, a variety of fabrics and design patterns could be procured by direct purchase or mail-order from the plethora of women’s magazines such as Godey’s Lady’s Book. Individual women would design and piece the top of a quilt, and then invite friends and neighbors for a quilting bee to baste the top, batting and backing together, making short and convivial work out of a task that could be long and tedious. Many times men joined these quilting bees after their work day, where food, music and socializing was enjoyed, making the bee a lively community endeavor.

A fine example of this kind of collective quilting exists in a Norwalk quilt now in the permanent collection of the Stamford Historical Society. Called the Hoyt family quilt, the name of each member of this group is sewn or inscribed in the center of the pieced stars.

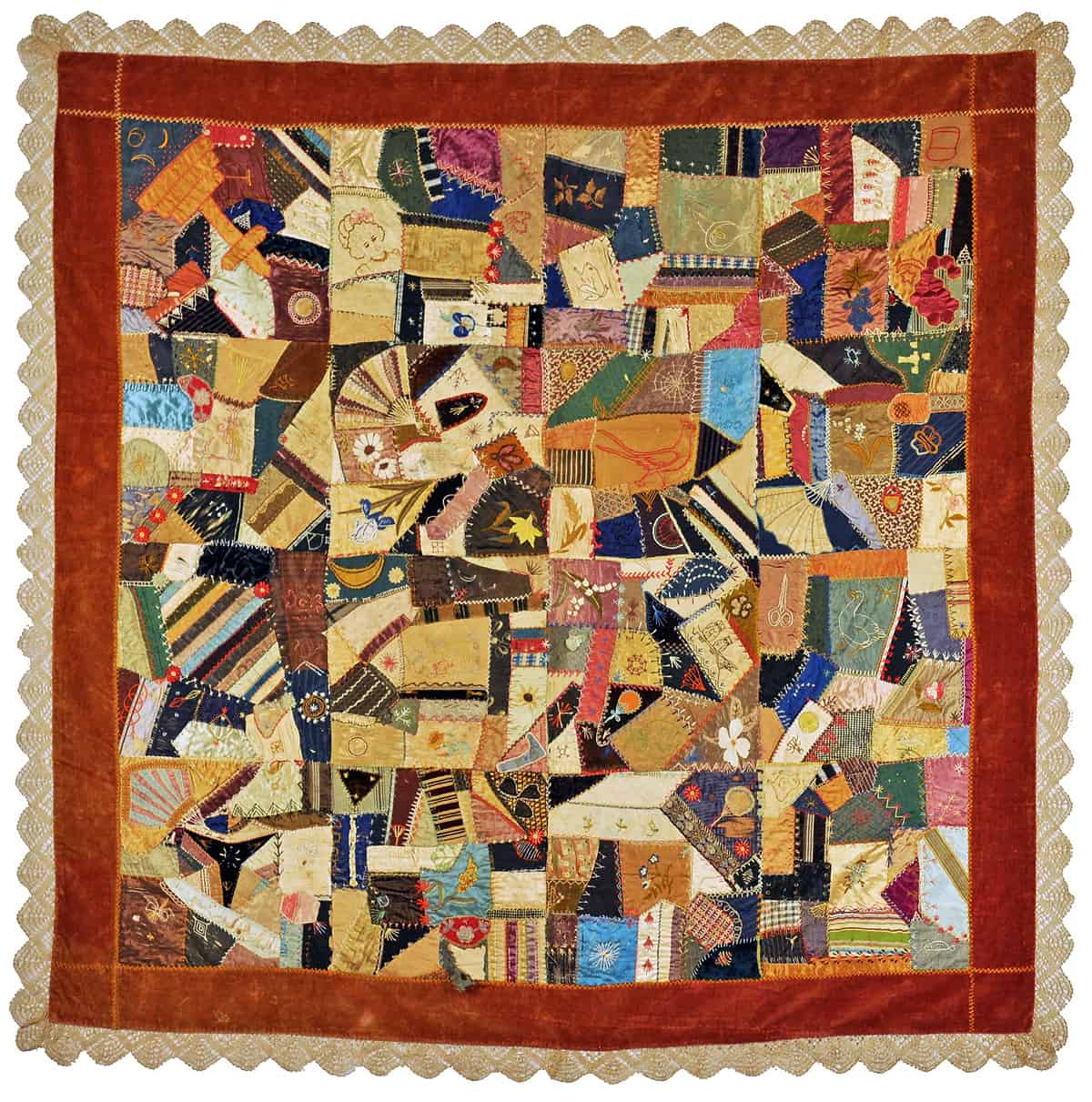

Another late 19th century version of quilting beloved today for their jewel tones, use of sumptuous materials and personalized patterns are crazy quilts, which developed in the late 1870s as a response to the fetish for the Far East, which came out of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago.

American culture became interested in the designs and aesthetics of Japan, seen in their prints, ceramics and clothing. Lockwood-Mathews Mansion and both the Norwalk and Rowayton Historical Societies have one each in their permanent collection, and each one carries information about the maker in its particular embroidered designs, many of which have personal meaning.

The Colonial Revival sparked a renewed interest in quilting during the interwar period providing a nostalgic look back to a time of perceived peace. The Norwalk Quilt Trail exhibition has several examples of quilts from this period. One is a large Yo-Yo quilt made with lavender borders and multi colored patches.

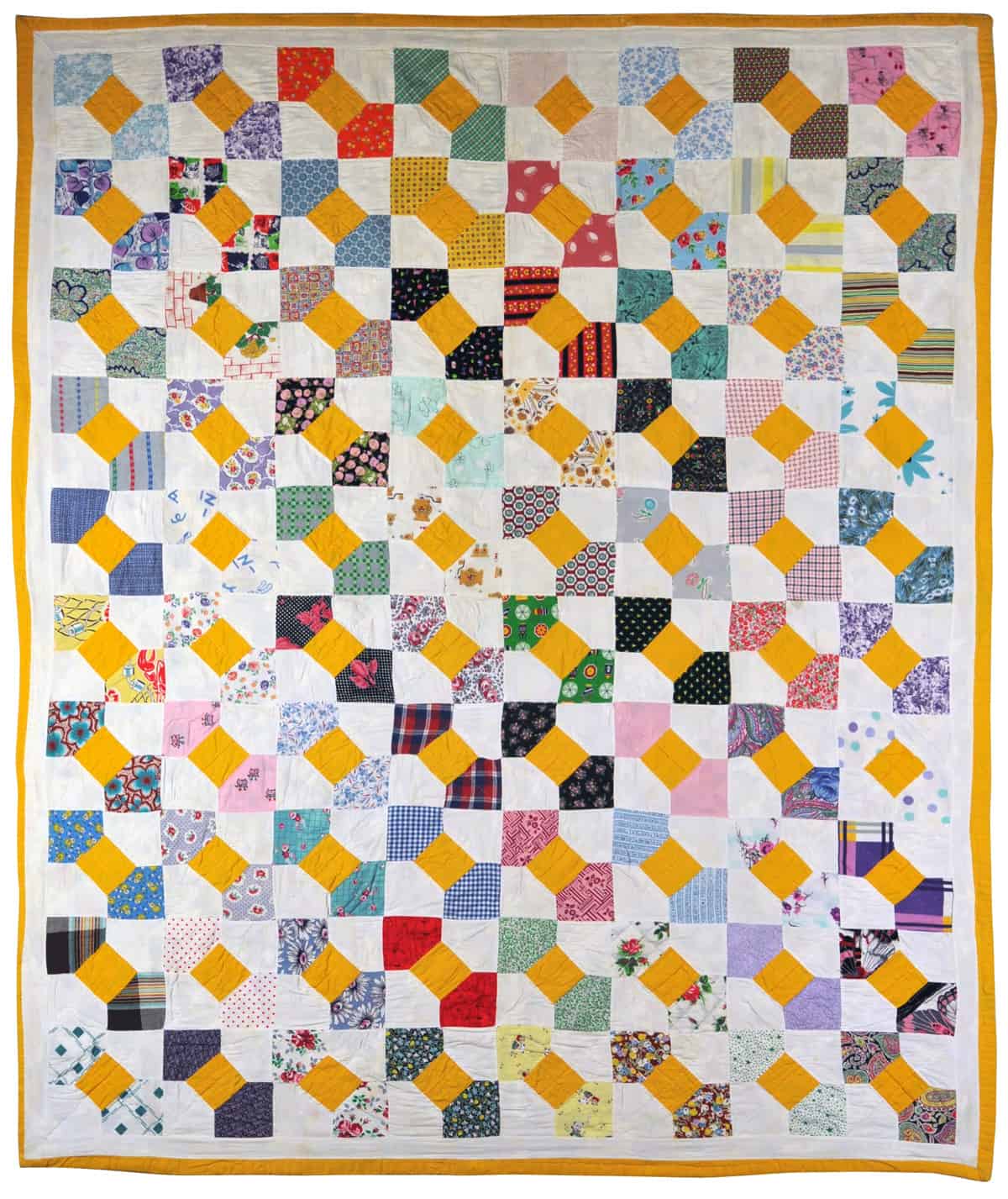

An excellent example made in Norwalk is seen in the yellow Bow Tie quilt, made about 1950 and, from the same hand, a series of cut-out shapes for a Tulip appliqué quilt that was never finished.

QUILT TRAIL VISUAL IDENTITY AND EXHIBIT DESIGN: SCOTT KUYKENDALL