They Remember

Between 1846 and 1847, Congregational Minister Edwin Hall recorded elderly residents’ reminiscences of the Burning of Norwalk. The following are excerpts of those memories from his book, The Ancient Historical Records of Norwalk, Connecticut, published in 1847.

Mary Ester St. John was a young wife of 27 years when the British burned Norwalk.

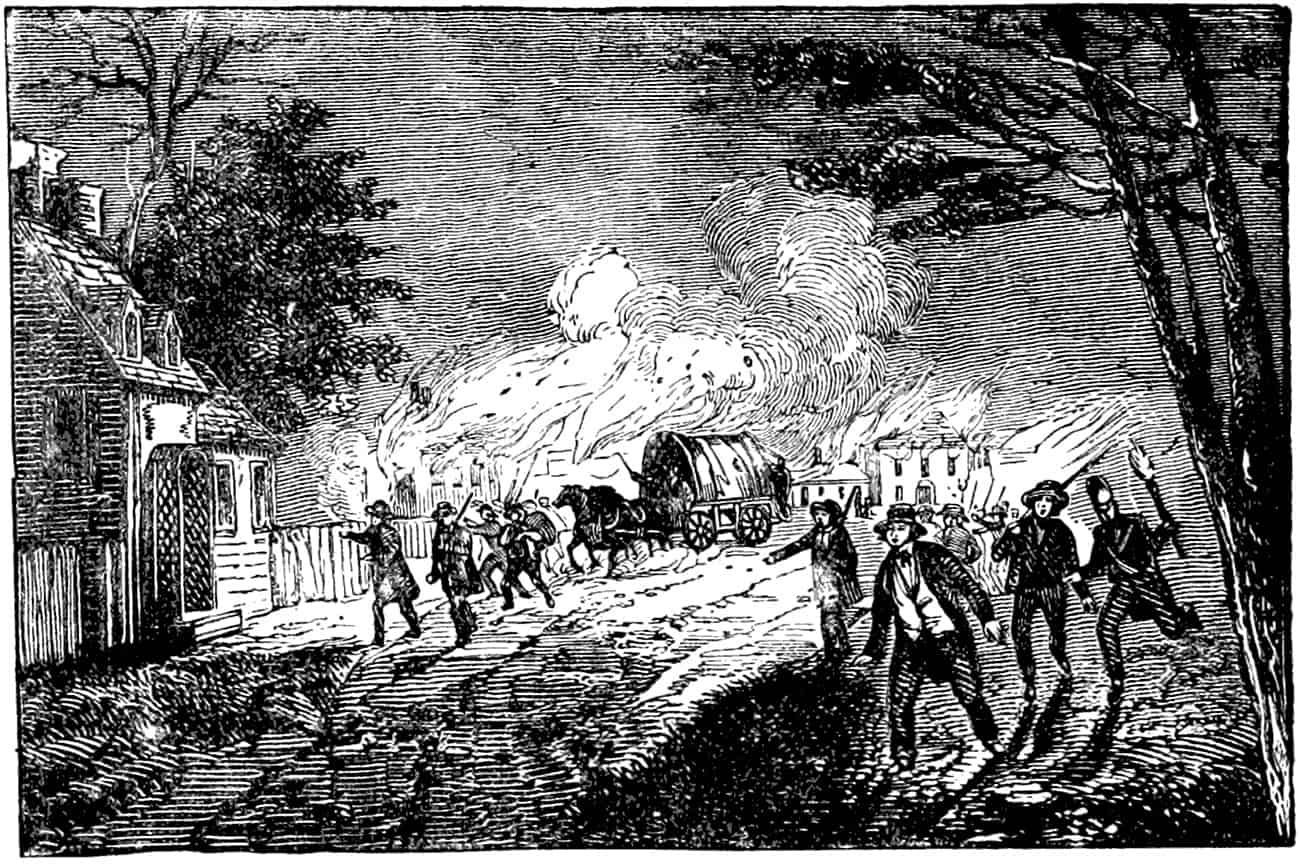

When Fairfield was burned (Sept. 7, 1779), her father was harvesting down in the Neck (Wilson Point). Expecting the British to come here immediately, they left the harvest; but when the British crossed to Long Island, her father rallied hands and went down to his harvesting. Saturday, near night, the alarm guns fired. Her husband rode down to the Neck, and returned; his horse was wet with sweat, as though he had been in the water.

Mrs. St. John and her husband and family, with what effects they could carry, went up into the woods, at the East Rocks. They had a bedstead, which they set up; milked the cows which they drove with them, drank the milk, and stayed there that night. In the morning, the guns were firing; the smoke of the burning houses rose. Her husband said, “The work has begun; they are burning the town.”

Miss Phebe Comstock, who was 16 years old at the time:

In cases of alarm, which was given by firing three guns in succession, the men left all and hastened to the parade. Such alarms often came. Her father would run in and say, “Now, girls, unyoke the oxen and turn them out,” and in less than five minutes would be off to the parade. They used to carry their guns to meeting; no more thought of going to meeting then without their guns, than we do now without our psalm books. The alarm at the burning of Norwalk came about daybreak. (She) went to the apple-tree (from the heights of which Norwalk could be seen very distinctly); saw the flames; heard the guns. Her father and four brothers were engaged in the defense; the “dreadfullest day she ever saw;” the guns kept firing a long time; “a dreadful fight.” She saw the “Red-coats” take up several of their dead or wounded, and carry them to their boats; saw the steeple of the meeting-house fall in.

Thomas Benedict was 15 years old at the time:

After the burning of Fairfield, the enemy was expected here. They came Saturday, while the people were harvesting. While he was driving the team, John Saunders, one of the Tories, came along and said, “O, boys, you are too late to harvest.” Saunders had finished his harvest. The sun was about two hours high, and Saunders was in high spirits at the coming of the enemy: as one of his sons was with the enemy, and he expected his property would be spared. But it was all burnt; and the other son with his negro went off with the enemy.

His family hastily packed up what goods they could; put them on the cart which they drove that night up to Belden’s Hill, to Thomas St. John’s. He saw the smoke of the burning of Norwalk in the morning. Heard the guns “pop, pop, pop, a good while.”

On his return to Norwalk, saw a British soldier that had been killed; Seth Abbott shot him as he was getting over a wall. “Now,” says Abbott, before he fired, “if I kill him, it will go right through his heart.” He fired, and the soldier fell backward, dead.

Nathaniel Raymond was 26 years of age when Norwalk was burned. He was a Corporal in The Guard and among the Connecticut troops when the British landed at Flatbush. He was 94 years old when he told his version to Rev. Hall:

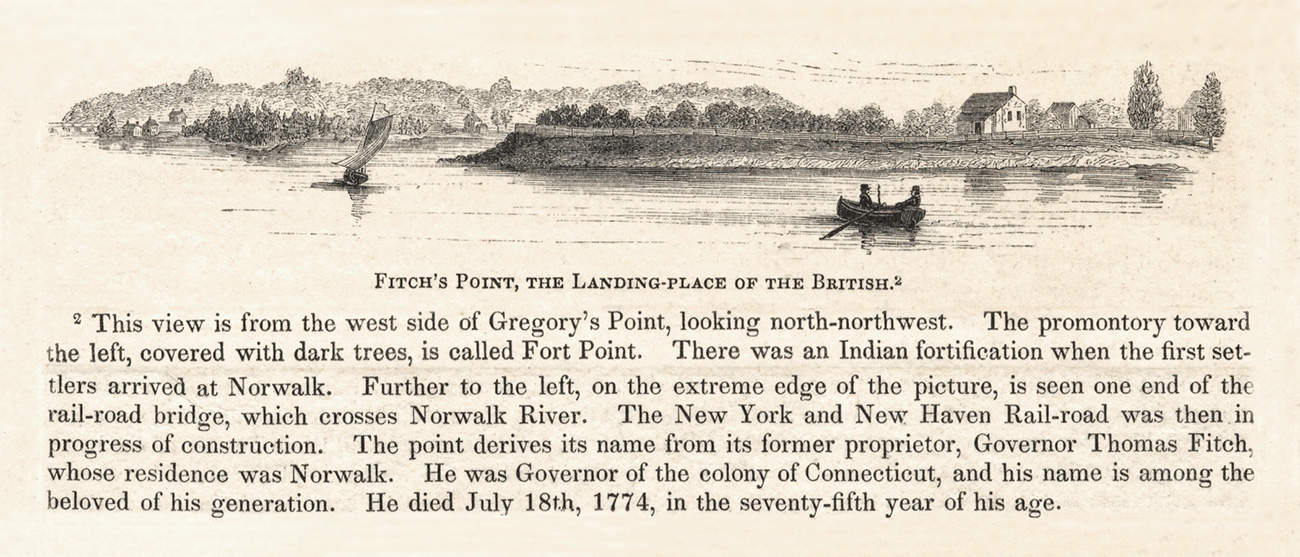

When the British came to burn the town, they landed at Fitch’s Point Saturday night. He carried such of his household effects as he could, down near the pottery called the village (South Norwalk) and hid them in a swamp; then carried his father and mother and some of their effects back some three miles, in a cart; returned, and with fourteen others, volunteers, under their own command, took arms, and went up to the hill where John Raymond lived. In the night the British fired a ball at them, at random. It struck the ground near them. Sunday morning the harbor was full of boats. They landed at the Old Well: chased the fifteen volunteers over John Raymond’s hill, (Flax Hill Road at the intersection of Taylor Avenue) and so over to Round Hill (intersection West Cedar Street and Taylor Avenue); dragging a field-piece, which they fired at the volunteers from the top of Round Hill. The volunteers fired at them from John Raymond’s hill. Saw Grummon’s Hill (east side of East Avenue at Morgan Ave.) “all red” with the British: there was “old Tryon and all his tribe.” The two parties of the enemy met near Grummon’s Hill, and went up to France Street, where there was a skirmish. There were about thirty American regular soldiers in town. Jacob Nash (his grandfather) was killed there. He was a regular soldier at home on furlough. Our men had an old iron four-pounder at the rocks (West Rocks), which the British took and spiked.